Is a fundamental change in steel prices in the works?

- Share

- Issue Time

- Feb 17,2022

Summary

Steel just keeps getting cheaper for fabricators and manufacturers—a trend with no clear end in sight. That’s good news for steel users, but not so good for holders of inventory.

Is a fundamental change in steel prices in the works?

A check of the market in the week of Feb. 7 by Steel Market Update (SMU) showed the benchmark price for hot-rolled coil (HRC) dipping below $1,200/ton ($60/cwt) for the first time in a year. As of the second week in February, the average hot-rolled price had declined to $1,190/ton, a plunge of $765/ton, or nearly 40%, since peaking at $1,955/ton in early September 2021. The downward trajectory is almost as steep for cold-rolled and coated steel products as well.

Steel producers and distributors enjoyed record profits in 2021 as steel prices spiked to historic highs when COVID and the government’s efforts to stimulate the economy threw steel supply and demand out of balance. In 2022 as steel prices normalize, mills and service centers can’t expect the same windfall. Their results will depend on how much longer, and how much lower, steel prices decline.

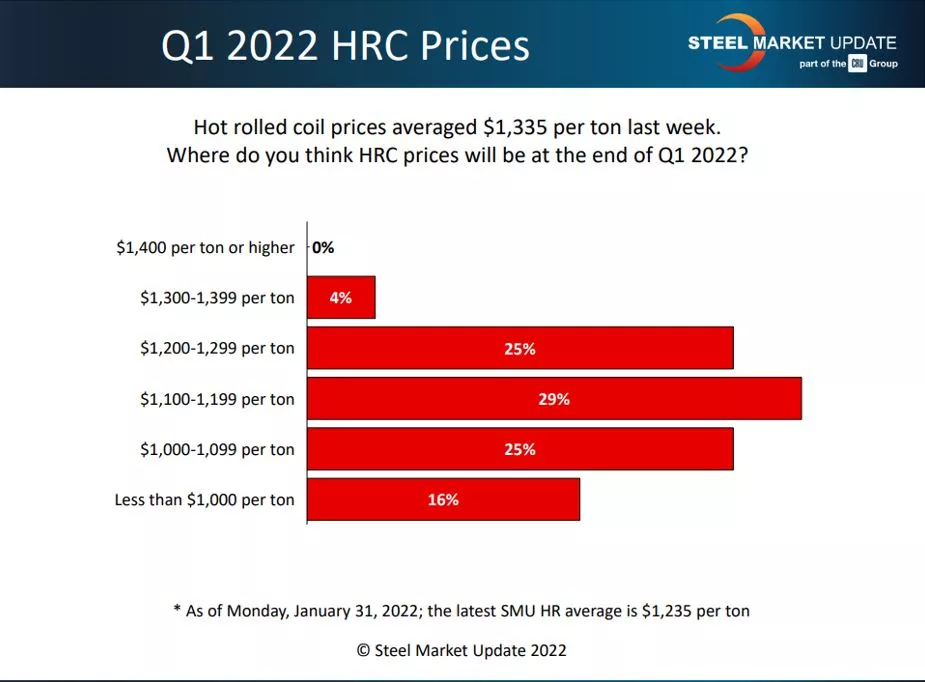

SMU surveys the market each week to keep track of industry trends. In early February our questionnaire asked: Where do you think HRC prices will be at the end of Q1 2022? Predictions were all across the board (see Figure 1), but 40% said they expected the price to be less than $1,100/ton. A weighted average of all the responses put the consensus prediction for the HRC price at roughly $1,125/ton by the end of March.

SMU’s questionnaire also asked: When will HRC prices find a bottom? More than half (64%) were betting the downward slide will be over by the end of Q2 (see Figure 2). But another 15% believed it could take until the end of the year, if not into Q1 2023, before prices plateau.

Lead Times as Low as They Can Go

SMU keeps a close eye on the average mill lead time, which typically is a leading indicator of steel prices. Longer lead times mean mills are busier and less likely to feel the need to discount prices to secure orders. During the peak of the market last May, lead times had stretched to 11 weeks or more.

As of early February, lead times had shortened to what is considered normal by historical standards, with hot-rolled lead times less than four weeks and cold-rolled and coated around six weeks. In other words, the time it takes the mills to make steel and process orders can’t get much shorter.

But the downward-trending steel prices are still double the historical norm and have a way to go before they level out. As a result, the next time lead times will have any real predictive value is when they begin to stretch out again. That will signal that demand at the mills is rising and prices are likely to firm up.

Optimists in the Majority

Steel buyers remain a surprisingly bullish bunch despite the plunging steel prices and lingering worries about COVID and the economy. SMU’s survey last month asked service center and manufacturing executives if they were optimistic or pessimistic about their prospects for the first half of 2022. About 70% considered themselves optimists. Is that glass-half-full attitude a good trait for surviving the current market or dangerously delusional?

Pessimistic comments from respondents generally focused on the uncertainty ahead and the difficulty in managing inventories during the ongoing price correction: